Last week, after over three years of flawless service, my PS3 developed the heat cycle fault that has ended the life of many of the original versions of the console. Luckily it wasn’t immediately terminal, so I managed to get the save data copied off of it in the short time it would stay on before powering down due to system failure.

That done, I had two options; pay £75 to get it repaired “professionally” or attempt to do it myself. The former came with a three month guarantee, the latter came free but with a chance I could do more harm than good. I decided it would be hard to trust a repaired system anyway, as it could go down again at any time, so decided that I’d crack it open and try to extend the life of it long enough to do a system migration.

For this you need two working PS3’s that you connect, with the clean system becoming a clone of the old system. This means you don’t have to re-download lots of content – in my case around 180Gb of data. The alternative is that you set up a clean system, copy the saves you’ve rescued to the new hard drive, and set about queueing items for download from the PSN store. Hence the system migration is preferrable.

I intended to repair my old one and perform a system migration, then retire the old one to limited use for the rest of its lifespan. Anecdotal evidence suggests that you only get a few more months out of it even if the repair is successful, which would explain the three month warranties you get offered by repair shops.

So, on a drab Saturday afternoon I set the old PS3 down on the kitchen worktop with a collection of tools to hand. I’d been fortunate enough to receive a quality set of screw drivers for fathers day in 2010 and these were just the job for taking apart a quality piece of Japanese hardware.

As each layer of the PS3 was peeled away, I couldn’t help but be impressed by the engineering. Ken Kutaragi might have fallen from grace due to the expense of producing the console created to meet his vision, but I could’t help but admire his intentions as I worked my way through the components. The Blu-Ray drive, the PSU, the Bluetooth and wireless antenae – they all nestle prefectly within the outer shell in a way that suggests the exterior form is more as a result of the internals than it is about aesthetics.

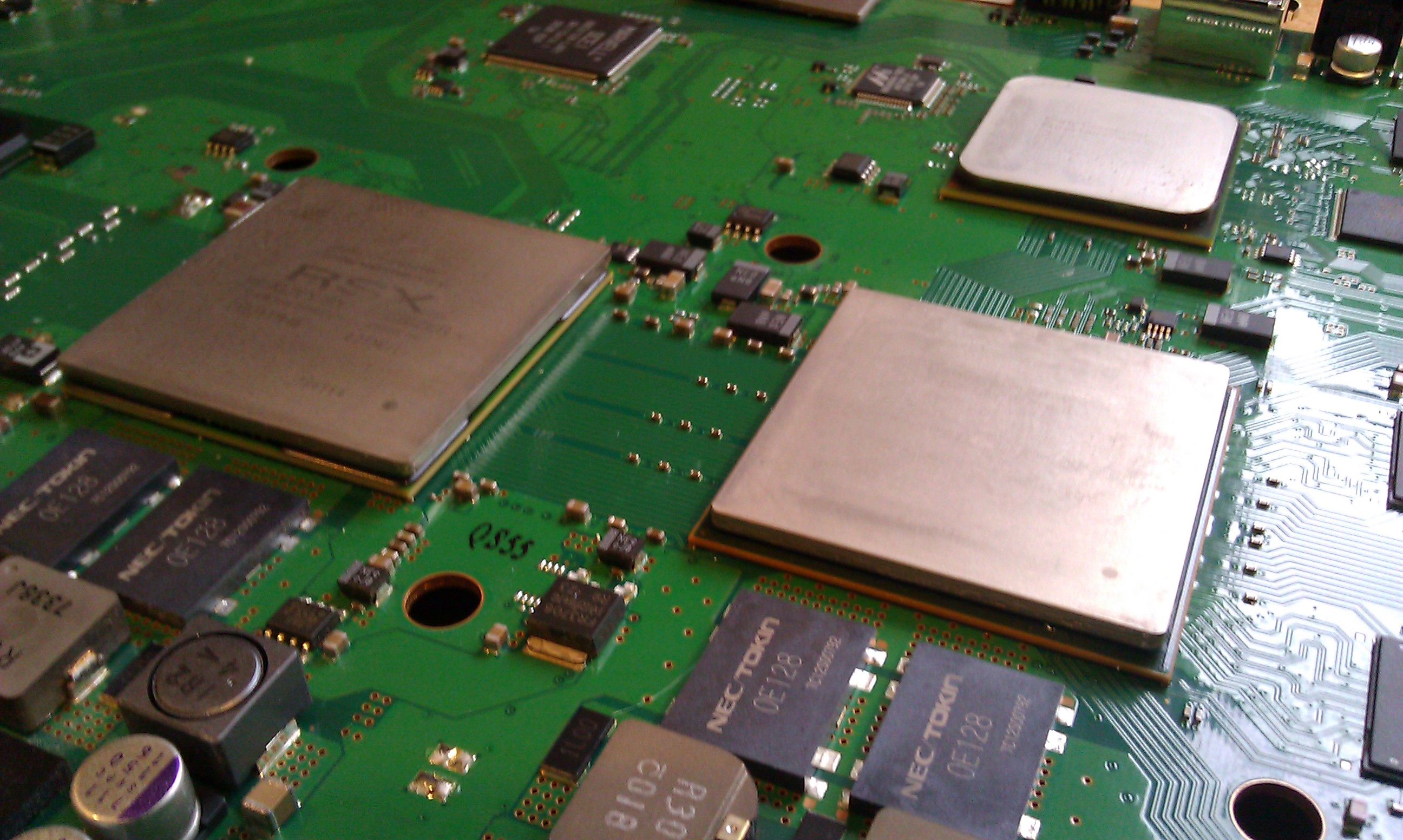

The heat sink and fan assembly just made me smile like clever solutions often do. How do you dissipate the heat from a pair of 90nm chips running at high temperature? Well, you do what Sony’s engineers did – you create a fan, heat pipe and heat sink assembly to do the kind of job that your competitors can only make a half assed nod to. That the weak point in the system is some cheap thermal compound and some poor quality solder is a disservice to the engineers who made the terraflop processor sit so readily on the shelves of mass market consumers.

By the time I was down to the motherboard I was doubting my chances of success. I couldn’t think of a logical reason why a guy in a kitchen with a heat gun would be able to right the wrongs in such a well built piece of hardware. Surely it was an insult to the fine folks who designed it that I should be even attempting this?

I was past the point of no return by then, so with the motherboard balanced on a metal worktop I cautiously began the heating process. Two minutes later I noticed the centre of the circuit board sagging under the weight of itself. I immediately backed off and re-thought how I was going to support the thing under its own weight, settling on an upturned metal dish to prop up the centre.

With the heat back on I worked between the Cell and the RSX, wafting the heat gun around the rest of the motherboars to avoid it warping. Things appeared to be going well, up until the 10 minute mark when something “popped.” I’m not sure if it was the dish or the metal worktop, but something had reached a tempetature that caused it to flex suddenly.

Right away I knew the implications and my heart sank. The whole point of the exercise was to melt and re-flow the cheap solder that had cracked over hundreds of heat cycles. By the ten minute mark it would have been liquid and any movement was a bad thing.

Deciding that there wasn’t much I could do about it I forged on, heating the Cell and RSX chips for a further minute each before beginning the cool down process. When that was done I left the board to settle to room temperature whilst we had some lunch.

It was at this time that the replacement console I’d ordered arrived. Rather than set the new one up, I left it in the box. No sense in getting distracted from the task at hand.

When I got back to it I was nervous about the reassembly. As my mother will testify, I’ve always had a talent for taking things apart, but it’s putting them back together has been my downfall. With some help from a YouTube video it went as well as could be expected, with my daughter helping to piece the last few layers together.

When I eventually attempted to power it up, I wasn’t entirely shocked when nothing happened. I suspected that the ribbon cable connecting the power & eject buttons wasn’t seated right, so I opened the case again and secured that.

It was clear that that had been the issue, too, as the next time the PS3 beeped as it sprung to life. The hope was short lived, though, as it then beeped several more times to indicate a system failure.

The fact the repair hadn’t worked was a disappointment for sure, but it wasn’t the end of the world. Considering the hundreds of hours of enjoyment we’ve gotten out of our original PS3 it was sad to see it go, but it would be hard to argue we haven’t had our money’s worth.

Hopefully our new PS3 will last a good long time itself. If it comes to it, I’d attempt to repair it if the same fault developed again some time down the line.